What’s Your Backup Plan, by David Rhoades – Making Marks | @MDWorld

March 19, 2015 Victor El-Khouri 0 Comments

“What’s your backup plan?”

I received that frustrating question for the (approximately) 1,456th time with some practiced grace. My grandma had asked for only the fifth time in a weekend, so she deserved some gentleness and understanding:

“Well, grandma, I figured if making comics doesn’t work out, I’ll start doing heroin and selling my body on the streets.”

…I wasn’t terribly good at showing gentleness and understanding at 17 years old.

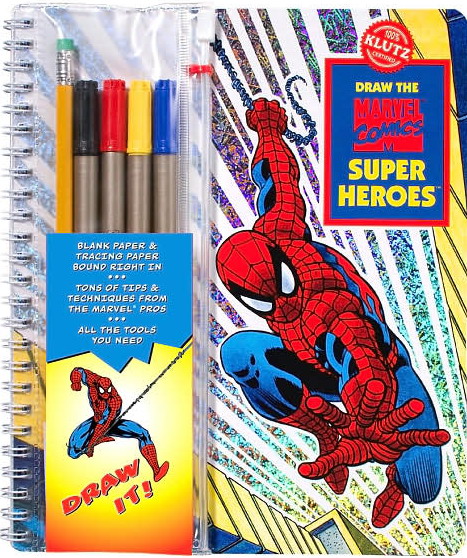

The truth is, I was tired of hearing that question over and over whenever family came around. When I was 7 years old, I begged my parents for a copy of Klutz’ How to Draw the Marvel Comics Superheroes, and shortly after working my way through the book, I boldly told my parents that I wanted to be a comic book artist when I grew up.

My parents, being good parents, wholeheartedly supported my decision on the spot. Just like they did when I said I wanted to be a chemist, a scientist, a detective, and even a detective-scientist (my tiny little heart nearly exploded when I found out there were people who used science to fight crime) all in the previous two weeks. I wanted to be a lot of things, and they let me explore all those options as a little kid.

The thing is…the comics thing stuck. Ever since I was seven years old, I’ve wanted to draw comics professionally. I bought instructional books, I asked for sketchbooks as gifts, I even asked my parents and grandparents for a combo Christmas/birthday gift of a $300 Kubert School correspondence course on penciling comics. One vacation, I begged my parents for a copy I saw of “Gray’s Anatomy,” an anatomy textbook I was sure would revolutionize my grasp of anatomical drawing. I was patient, I was driven, and it was around the time that I was 12 years old and drawing through yet another ream of computer paper that my parents started to take my ambitions pretty seriously.

It was around that time that my snobbish but deeply-concerned grandparents began asking what I was really planning to do with my life. “Surely you’re not really going to devote your life to the illegitimate, bastard artform of comics!” they seemed to say with their tone. I don’t blame them — comics is notorious for being a career of long hours, little margin for health, and historically underwhelming pay.

I think what they didn’t realize is that all their questions eventually solidified my convictions and ambition. See, I was a stubborn boy, but I wasn’t stupid. I didn’t fool myself into thinking that comics was miraculously going to explode into a culturally relevant, artistically vibrant, and increasingly lucrative industry with ties to all other branches of entertainment.

(I mean, all those things actually happened, but this was early 2001 — it was a simpler time).

I didn’t fool myself into thinking that was just going to happen because I wanted them to. Their questions made sense to me, and when I was asked point-blank to seriously consider the viability of my dreams (again, at 12 years old), it set me face-to-face with my anxieties instead of letting them fester. When I faced the possibility that I wasn’t likely to make a whole lot of money, when I faced hard questions about how I was going to support a family, when I found myself drawing at my desk for hours and hours away from my friends, I held onto a vital truth: I was doing this because I love drawing, I love writing, and I believe in the power of stories to change us.

Their questions, instead of making me doubt my path, taught me to hold on, to keep leaning into the wind of difficulty. If the road gets rougher, then make my legs stronger. If the hill gets steeper, run harder. When doubts creep in, keep my shoulders down and grit my teeth until my jaws ache.

In short, their questions prepared me to become a comic book artist.

It’s good to wrestle with doubt. It’s good to wonder if we’re going to make it. It’s not because it’s pleasant or comforting, but because it forces us to understand why we’re doing what we’re doing. If your answer goes beyond comfort, goes beyond external reward, then you’re prepared for the long haul. I’m excited to see what you’re going to do, and I hope you’re excited to see what I’m about to do too.

So, it’s my honor to ask you…what’s your backup plan?

Show your work.

David Rhoades writes and draws stories, and he teaches junior high kids how to do the same. He’s been working with Michael Davis since he was 17 years old, around the last time that his grandma ever asked him about his “backup plan.”